If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about Outside Online's affiliate link policy

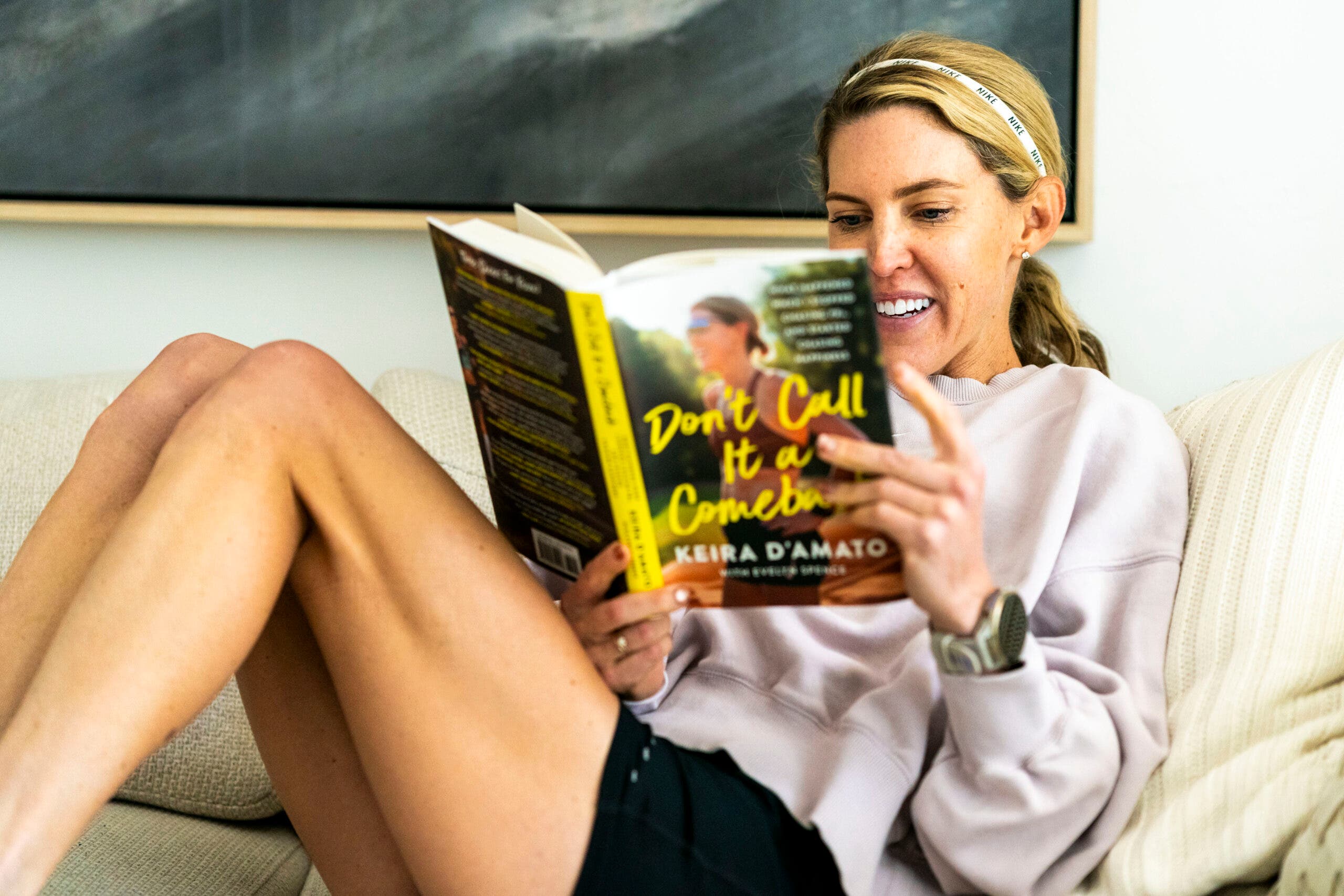

Keira D’Amato on How Her First Win as a Mom Reignited Her Competitive Fire

(Photo: Gabe Mayberry)

When I started moving again in the fall of 2016, I had wiped my slate clean—I was back at square one, holding my drawing board. At first, my daily goals were as easy as putting on running clothes. Sometimes I focused on mileage or time on my feet, but often it was more about the experience: running somewhere new. Running with a friend. Running to a coffee shop. If you come up with things that excite you, it doesn’t matter if they’re seemingly small. Hey, even taking the day off is a win—you’re setting yourself up for a stronger tomorrow.

Though running illustrates this so cleanly, it’s a lesson I’ve carried over into the rest of my life: if you’re celebrating every day, you’ll find yourself more fulfilled. Winning isn’t usually considered an emotion, but in my experience—and maybe Charlie Sheen’s—it certainly can be. As I met my goals, I was becoming a more confident person outside running, too. A more confident mother. A more confident partner. I could handle Anthony’s absence. I was proud. Overcoming fitness obstacles had benefits that spilled over to every other part of my life, changing my outlook and my personality. The impact on my mental health was profound. To me, working toward things, becoming more goal-oriented, was making me happy.

Happiness isn’t an enormous reward at the end of the road—you arrive, and then ta-da, you’re finally there, happy at last, and for keeps. Happiness is continually moving toward something with purpose, not sitting on your laurels. For a while, I thought I was happy not having to get up and run in the rain. But you know what it’s like when you see a friend you haven’t seen in five years, and as soon as you lay eyes on the person, you start to cry and realize how much the friend meant to you?

That’s how I felt about running. The goals and the challenge and the grit were bringing me back to my roots and my heart.

Sacrifice, dedication, and discipline: that’s what was making me happy.

I was chasing happiness, but happiness was the chase. On New Year’s Day 2017, I ran my second official race of Round Two: it was called the First Day 5K, put on by the Richmond Road Runners Club. People don’t think of Richmond as a running hotbed on the level of Boulder or Flagstaff or even New York City, but RRRC is one of the largest clubs in the country (2,500 members, 20-odd races a year), and it has an avid, inclusive, unpretentious vibe. A 19-year-old local kid, Cole Shugart, won that day—which doesn’t matter, except that a few years later he helped pace me while I trained for the Houston Marathon. Anthony was tenth, finishing in a solid 18:27 (that’s just under six minutes per mile). And I crossed the line fourteenth overall, second for women, and broke 20 minutes for the first time in almost a decade.

The girl who beat me, Josey Rupert, ran 18:22 to my 19:37—which is a sizable difference. She was 23, I was 32 (also sizable, and mathematically pleasing). I was in awe of her and thought to myself, I’m never going to run that fast. But I stalked her during my cooldown and said, “Hey, I’m new to the area” (relatively true) and “Would you want to run with me?” It was kind of like community service for her, but she agreed, and she showed me some new routes to run—places like the Capital Trail, a 51- mile paved pathway from Great Shiplock Park in Richmond all the way to Jamestown.

Until I approached Josey, I hadn’t been confident enough to connect with any other runners in person. I didn’t want to ask anyone to run with me, then have to take 25 walking breaks. (Even though no one has ever minded.) My ego was making assumptions about other people’s egos. But Strava helped me feel like I was a part of something.

And the Richmond women I knew virtually had a knack of showing up in the same physical locations as me. It was less intimidating to walk up to a stranger and say, “Hey, I see that we run in similar areas, so maybe we can get together sometime?” I made a couple of real girlfriends from Strava girlfriends—like the movie Her, but less unsettling.

Now, unless I’m doing a serious workout, I love running with people—it isn’t a desperate escape like it once was. (Regular old escape? Sometimes.) I absolutely pinkie promise that I don’t mind stopping to walk. Try me.

This new sense of community fed straight into my sense of winning—my online “friends” were becoming real, in-the-flesh connections, and the plain act of meeting with them to exercise was a tangible accomplishment. Your goals don’t have to relate to podiums and splits; they can be emotional. Social. During this time, Anthony was gone, so running with people fed my growing need for fitness and human, adult relationships. I don’t know whether it was because I was in better physical shape or I’d gotten past the newborn stage with Quin (translation:slightly more sleep), but I found myself with a smidgen of space for other people and their reciprocal energy.

A week or two later, not long before Shamrock Marathon race day, I entered the Sweetheart 8K, another local RRRC race. My mileage was up—one week, I hit 50 total miles—though I still wasn’t purposeful, other than desperately wanting to avoid a repeat of my Missoula disaster. Only a few hundred participants signed up, but it was chip- timed and official. The course started at the Urban Farmhouse in Midlothian, then rolled over roads and trails past the colonial homes of Walton Park and the neat lawns of the Grove and through woodsy Midlothian Mines Park. And I mean rolled. It was a hilly race, and the last half mile climbed a punishing incline. Somehow, by the time I reached the bottom of the final slope, I found myself in first place for women. I couldn’t believe it—and also couldn’t believe how much I was hurting.

All the fight went out of me. I guess I was just apathetic about coming out on top. Up until that moment, at least in Round Two, running was cool and everything—as long as my body felt relatively strong. This? My legs were cinder blocks. My lungs were heaving. Partway up the hill, I was in the middle of talking myself out of trying when I saw Linda D’Amato, my mother-in-law, with her ubiquitous camera. She was kind of watching my kids. Tom was kind of watching my kids. Anthony had already crushed me. I experienced momentary relief: Linda would feel sorry for me. She’d see that I was red in the face, panting. She’d delete the bad photos—if you’re a runner, you know how unflattering some action shots can be. She’d give me some comforting, golf- style applause. I expected her to call out, “It’s OK, honey, you’re doing your best!”

As I ran by her, she screamed, “Get your butt moving! Get your butt moving! She’s closing on you! You can win!”

It was anything but consoling; it put the fear of I don’t even know what into me. I glanced over my shoulder and saw that, yes, she was gaining. I dug deeper. It burned. And I managed to win—with seven seconds to spare before she caught me. It was my first victory as a mom. My whole family was there to witness it.

I had a revelation about Linda that day: She’s never going to pity me, or you, or anyone else. She’s going to champion you, but she’s a fiery competitor. And she brought my inner competitor back out of hiding. I mean, remember the way I played kickball? She knows what kind of person I am; she held me to my own standard and kept me accountable.

Feel sorry for ourselves? No thanks. We work through the pain. It’s so tempting—when things aren’t going the way you want and you’re suffering at the end of a race (or workout or hike or match or game) to convince yourself that you don’t care. It almost happened to me in the Sweetheart: I persuaded myself that I didn’t care because I was crumbling in the face of the discomfort. When you’re exhausted, your gut reaction is often: It’s fine. It doesn’t matter. Linda reminded me to talk back to that voice. (Correction: during the Sweetheart, she became that voice on my behalf.) Even now, I have to tell myself that I’m not going to crumble.

A lot of us, in these moments, even manage to convince ourselves that we’re not deserving of our ambitions and dreams. We need to remind our inner gaslighter that our hopes are important and worthy. Acknowledge that, yes, this is my goal. Under all the layers and Cirque du Soleil–worthy mental contortions, down where the deep shit happens, it does matter. Even if it’s a small objective, it’s OK that it feels like a big deal.

When I pretend like a race carries no real weight for me, that’s when I fall apart. The fire sputters. When I remind myself that I want to fight for something and hold myself to what I set out to do, I run my best. To me, running is a unique sport because there are a seemingly infinite number of reasons to run. Everyone has a different why—and having a clear why makes it a lot easier to wake up early before work, or to lace up your shoes when the forecast calls for a bomb cyclone, or to set aside specific blocks in your schedule. A why keeps you focused. Energized. Moving forward. Your why doesn’t have to stay the same (in a lot of ways, it shouldn’t). Mine—as you know, if you’ve been reading until now—has been all over the place, from improving my mental health to losing weight to getting the heck out of the toddler bedlam inside my house.

When people ask you what on earth possesses you to run in circles over and over just to get back to where you started (which is kinda what running is), your why is your retort. Not that anyone else needs to know. My genius uncle, John, kindly reminded me that I work awfully hard to technically have a velocity of zero. Velocity equals Distance over Time, and if D equals zero, then . . . wait, I’m losing you.

I can’t remember if I raised my arms up and flashed V-for-victory signs when I won the Sweetheart, but I probably did. It has become my calling card and my vibe. Track down a photo of me at the end of the Missoula Marathon in 2013, and there I am, celebrating. Look up an Instagram post from the 2023 World Championships—where I finished seventeenth, with a ragingly painful hip flexor—and I’m raising the roof. Most elite runners save their big gestures for big moments; they’re too proud to celebrate simply finishing a race. I used to be that way: What joy is there in coming up short? But once I stepped away, I had a little epiphany. In a race with ten thousand people, only one person can win. Does that mean only one person can be psyched? Hell, no. We’ve all run the same distance. When I was part of the pack, I still felt a ginormous sense of accomplishment if I managed to finish. I mean, most of the excitement is as uncomplicated as now I can be done running. Yet your moment at the end of the race means that you showed up. You didn’t quit when you really, really wanted to. You persevered when things weren’t going well. Making it to the end of a bad race is often more of a success than winning the perfect one.

From Don’t Call It a Comeback: What Happened When I Stopped Chasing PRs, and Started Chasing Happiness by Keira D’Amato with Evelyn Spence. Copyright © 2025 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.