No-Fall Terrain and No Course Markings: PTL is the Hardest (And Arguably the Best) Event During UTMB Week

(Photo: Peter Maksimow)

At 8 a.m. on the last Monday of August, 119 teams of two or three trotted surreptitiously out of Chamonix, France.

Onlookers, here for UTMB week and the spandex circus that surrounds it, couldn’t quite figure out what was going on.

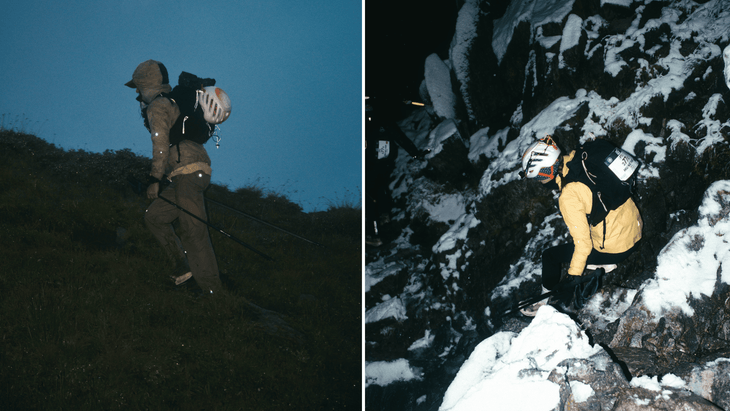

In lieu of minimalist hydration vests and lightweight trail “super shoes,” these runners were schlepping bulky packs with helmets, climbing harnesses, and crampons strapped on the back. They looked very little like competitors in the seven other high-octane races throughout the week—and for good reason.

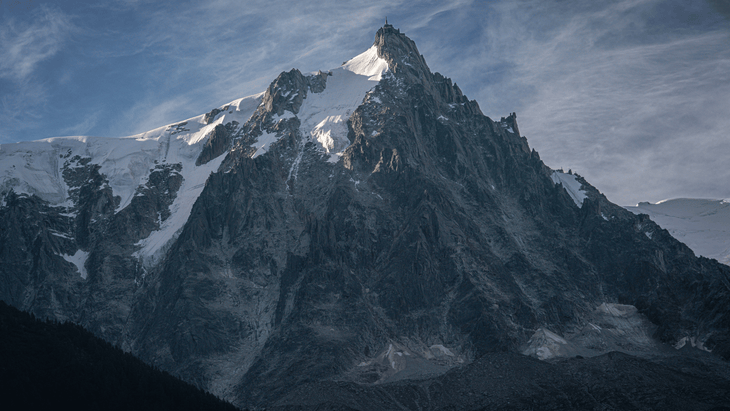

At 300-plus kilometers (186 miles) and featuring ample no-fall technical mountaineering terrain, PTL is about as far from the other events of UTMB week as you can get. And yet, they coexist happily under the same tent.

Similar Reads

The “Petite Trotte” That’s Anything But

Officially, the start of PTL marks the opening of UTMB week— those iconic seven days at the end of August when this French mountain nestled below 15,770-foot Mont Blanc comes alive with 10,000 trail runners racing among eight different events, plus many multiples more in family, friends, and fans.

In UTMB’s world, PTL is an outlier. It’s run in teams of two or three runners. The course changes annually. (The 2025 loop totalled 311 kilometers with over 82,000 feet of vert.) And it’s not marked, either—you’ll need to carry a GPS unit to follow the route. Runners need to monitor their two-way GPS trackers, too, because it’s not uncommon for the course to shift to one of several alternative routes mid-race, as race organizers monitor ever-changing high mountain weather conditions and the progress of the teams.

PTL has other quirks, too. There are few aid stations and just two major “life bases.” Participants bring cash, and can stop anywhere they like, as long as that hut or shop is also available to other participants. Several partner refuges provide warm meals for participants, who can also grab a few hours of sleep. At any of the other several dozen mountain huts along the course, participants can buy meals.

And unlike the other events, PTL is managed by an independent, all-volunteer committee whose headquarters during the event is Chamonix’s Maison Montagne, or Mountain House, the town’s nonprofit hub for climbing and mountaineering information. There, a safety team monitors screens that track each team and weather conditions, as well as field calls from participants.

No lottery entries—UTMB calls them “running stones”—are needed to get into PTL. Instead, applicants answer a detailed questionnaire and send in their outdoor resume, being sure to include experience like longest mountain trail races, hardest rock and ice climbs, and the highest peaks summited.

That’s what I did, along with Paul Spackman and Giles Ruck, last winter when we decided to apply for PTL as a team. After five decades of playing in the mountains, I had accumulated some high summits and long—OK, very long—trail races, like Tor des Géants, the 330K race in Italy I’ve completed three times. And yet I was the novice on our team. The other two have summited Everest, and Ruck completed PTL in 2018.

We got into the race, and six months later we were ready to roll—or so it seemed.

Is That Your Femur Sticking Out?

Completing an event like PTL requires several things. One, you need an absolutely rock-solid “why.” This is a reason why you are there that will not desert you in your darkest moments.

Two, you need the skills and resilience to cope when things go wrong—which, over the course of five to seven days of continuously pushing hard in the Alps, they will, and multiple times. And finally, you need solid fitness, a willingness to suffer, and good health. All those elements need to be in abundance on race day.

It was that last piece of the puzzle that eluded me.

At bib pickup the day before, I was vaguely nauseous, see-sawing between chills and a fever. I told myself it was food poisoning, and would quickly pass. But I also knew that a stomach bug had infiltrated the valley. And so the next morning I found myself at the start line, telling myself, “If the first hours don’t go well, I’ll just drop. No pressure.” Which is a violation of one my cardinal rules for starting such events, learned from internationally-acclaimed endurance athlete Stephanie Case, who told me once—perhaps less than half joking—“You have to be able to tell yourself, ‘I’m not stopping unless my femur is sticking out of my leg.’”

Leon’s Little Walk

How did something so incomprehensibly long and challenging enter the UTMB lexicon of acronyms? The origin story traces back to 2007. Four years after the first edition of Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB), race organizers were searching for a way to balance a burgeoning elite field with UTMB’s mountain spirit. But, villages around Mont Blanc were still learning to manage the newfound popularity of the races, and they didn’t need additional impact.

UTMB co-founder Michel Poletti zeroed in on an idea. “We wanted a big adventure, with the solidarity of a team, and based on the principles of self-sufficiency and autonomy,” he said. “And from the outset, being super fast was not part of the spirit of PTL.”

The organization wanted an event that felt accessible and friendly but also required deep mountain skills and experience. The name would be important, too. Proclamations like, “world’s hardest!” and prefixes like “mega” wouldn’t fly. This was not going to be the UTMB Death Race. At one of the early organizing meetings, jovial pastry chef Leon Lovey half joked about calling it a “little walk”—in his French-speaking corner of Switzerland, that would be a “petite trotte.” The joke stuck, and since Lovey suggested it, he got tagged. Result? The Petite Trotte à Leon, aka Leon’s Little Walk.

From the outset, the course was designed by Poletti and his friend from the other side of Mont Blanc in Courmayeur, Italy, Alberto Motta. (Motta went on to found Tor des Géants.) A key goal was to highlight lesser-known areas and huts around the Mont Blanc range that the UTMB races miss. To build that goal into the event’s DNA, they decided the course would change every year.

In July of 2008, Poletti and Motta set off from Chamonix, scouting a route they had in mind. They explored high passes and trail-less ridges, covering 240K. “We were two guys, not talking much, moving together in the mountains. We had a wonderful time,” Poletti recalled. And when they arrived back at Place du Triange de l’Amitié, in front of the mayor’s office in Chamonix, PTL had its first course.

During that first summer, Chamonix retiree Jean-Claude Marmier stepped in as race director. Marmier was a legendary mountaineer with tough first ascents to his credit. During an impressive mountain career, he created France’s elite high mountain military unit, the GHMH, was president of the French Mountaineering Federation, and co-founded alpinism’s most prestigious award, the Piolets d’Or, or Golden Ice Axes.

“The PhD of Trail Running”

In the ensuing years, PTL has stayed true to its mountainous, adventurous DNA. Built into such an event is an unavoidable risk, and despite rigorous safety requirements, the race had its first fatality in 2022, when a Brazilian participant fell 30 to 50 feet during the night. The fall was the sort of accident that could have happened to anyone traveling in the mountains.

“You have to find a good balance,” Poletti said. “Organizations need to be fully responsible, but participants have to understand there are risks with such events. PTL is part of the biggest trail running event in the world. But it’s not trail running. It has the spirit and values of trail running, but it’s an adventure race, a true mountain event.”

While a large and growing professional team oversees UTMB’s races and the associated UTMB World Series, PTL is still managed by a tight committee of eight volunteers. The group is overseen by one professional staffer, Baptiste Lassenssion, who coordinates the volunteers with the rest of the UTMB organization. The committee meets monthly, with the associated course committee exploring routes for the future, and working hard to secure the dozens of landowner permissions that are required annually for the huge loop.

As the snow melts from the high mountain passes each June, PTL’s volunteers head into the mountains to analyze the proposed route. When they’re satisfied the route meets their criteria, they share it publicly—but not until ten days before PTL starts, in part so participants coming from afar can be on an equal footing with locals, who otherwise could recon the route all summer.

What kind of person would take part in PTL? Lassenssion puts it this way. “It’s something you do when you’ve done everything else,” he says. PTL, in other words, is trail running’s PhD—and one that requires more than a few prerequisites in mountaineering. That observation is consistent with PTL’s median age, which at 45.4 in 2025 was two and a half years older than that of UTMB.

Cold, Tired, and In Survival Mode

This year, 119 teams started PTL, with names like The Taiwan Trailblazers, The Flying Cows, and The Provence Wild Boars. Eighty-nine of them crossed the finish line in Chamonix within the 151 hour time limit, for a drop rate of about 25 percent. While PTL skews heavily male, this year’s event featured an all woman team, The Aravissantes, from the nearby Aravis mountains that separate the Chamonix valley from nearby Annecy, France. They finished in 145 hours, 52 minutes, and 38 seconds.

Kirra Balmanno, a Chamonix resident, veterinarian, and professional trail runner, teamed up with Hong Kong friend Michael McComb for a mixed-gender team. Balmanno, who tackles big solo mountain efforts annually in the Himalaya, was drawn to the adventurous spirit of the race.

“I was crewing a friend for UTMB a few years ago when I saw two guys with helmets climbing up a crazily steep hill,” she said. “They were having what looked to be a super hardcore, transformative experience, and I really wanted to be a part of it.”

But being part of PTL required Balmanno to overcome her massive fear of heights. “PTL really scared me, but it also sparked my curiosity. I like to overcome my fears,” she said. “I think it makes me a better person.”

Like the topography over which she travelled, Balmanno experienced big highs and low lows. “I went in with a mindset of trying to embrace the whole experience, which includes a lot of suffering,” she said. “I remember being about 10 hours in and feeling a huge dose of endorphins.”

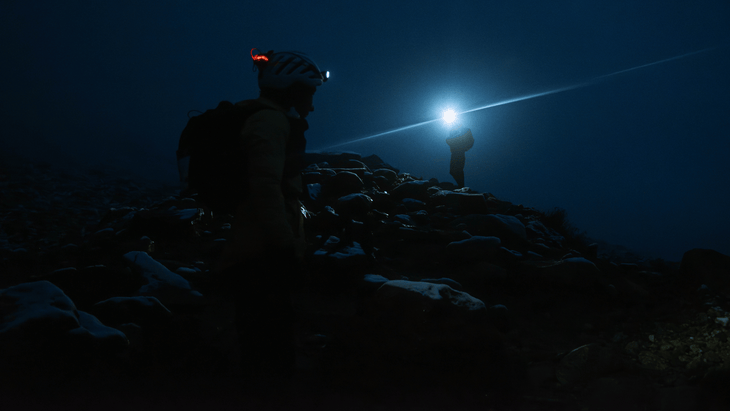

The highs don’t last forever, though. This year’s PTL included a hefty dose of poor weather, forcing race organizers to divert teams to lower elevations and less exposed routes. “We did go over a few passes during storms,” Balmanno said, noting that the winds gusted to 50 miles per hour.

“We were cold and tired, just trying to navigate,” she continued. We went into survival mode. We got really focused and just did what we had to do.”

Through it all, PTL’s team of volunteers supported the runners at the course’s limited number of aid stations and meal stops. “The volunteers were incredibly kind, supportive and helpful. They were very sweet to us,” Balmanno said. “That was a really beautiful part of the PTL.”

While the PTL committee downplays speed and rankings, it was hard not to notice brothers Jules-Henri and Candide Gabioud, residents of the Swiss mountain village of La Fouly right on the course of UTMB. This year, they crossed the finish line of PTL in just 78 hours—a blazingly quick time made even faster by the implementation of multiple alternative routes due to severe weather. It was their fourth time finishing PTL before any other team.

The Soul of the Mountain Spirit

My own PTL came to an untimely end, thanks to a virus that sapped my strength when I needed it most. But it didn’t wrap up before I glimpsed a bit of the mountain spirit that Poletti seeks to preserve. High above Les Contamines, France, deep into a late summer evening, I alternated clipping carabiners onto a metal cable that kept me attached to the mountain. I was moving quickly through big mountain terrain, surrounded by stars and rock and glaciers. In the distance, headlamps traced a line to the remote, tiny Refuge de Plan Glacier, elevation 2,680 meters (8,792 feet), our next destination. I was, for a brief moment, exactly where I wanted to be.

In an era of more than 50 UTMB World Series races, plus the Finals in Chamonix that make for a global trail running spectacle, it’s easy to wonder, “Why bother?”

PTL is challenging to organize, filled with risks, and about as distant from being a profit center as one could imagine. (The €1,600 entry fee is over three-and-a-half times that of UTMB, with €150 of that going towards trail maintenance and €13 for membership into UTMB’s “Friends of UTMB” association. And yet thanks to the field sizes, PTL brings in less than a fifth of the gross revenue. Its time limit of 151 hours is also over three times longer than the next race, UTMB, at 46.75 hours.) But maybe that’s exactly the point. Events like PTL bring us back to the heart and soul of the mountain spirit, and remind us of what matters.

“When you come out the other side, you realize you’re part of this mythical event. You are now part of this little community with a shared passion for this crazy, wild adventure,” Balmanno said. “I can’t wait to do it again next year.”

Doug Mayer lives in Chamonix, France, and founded the trail running tour company, Run the Alps. His most recent book is The Last of the Giants, about the 330K-long Tor des Géants trail race.